The Introduction

The transcribed seminar

The essay on globalization

This is vol. 3 of the Art Seminar series. In it, about thirty scholars discuss the question of the worldwide dissemination of the discipline of art history, including Shelly Errington, Friedrich Teja Bach, Cao Yiqiang, Shigemi Inaga, Craig Clunas, Suman Gupta, David Carrier, Matthew Rampley, Keith Moxey, Andrea Giunta, Sandra Klopper, Barbara Stafford, Charlotte Bydler, Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Mariusz Bryl, Keith Moxey, Suzana Milevska, Shelly Errington, and David Summers. It was one of the first books of its kind, and like a number that followed, it often conflates the globalization of art with the globalization of the discipline of art history.

The essay uploaded here is a starting point for these questions, weighing arguments for and against the notion that the practices collectively known as art history have become global. Since the book Is Art History Global? there have been a number of publications on the globalization of art, but only a few on the globalization or spread of art history. My last word on that subject is in The End of Diversity in Art Historical Writing (2020).

The following are from lectures on the subjects broached in the essay in this book.

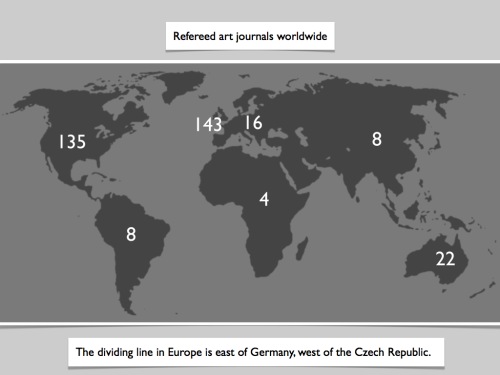

First is a map labeled with art history departments worldwide. I did this research in c. 2007, so it will have changed, but the proportions might not be that different:

Refereed art journals worldwide yields a similar pattern:

Here I have divided Europe east of Germany and west of the Czech Republic,

to reflect a sharp falling-off of peer-reviewed journals.

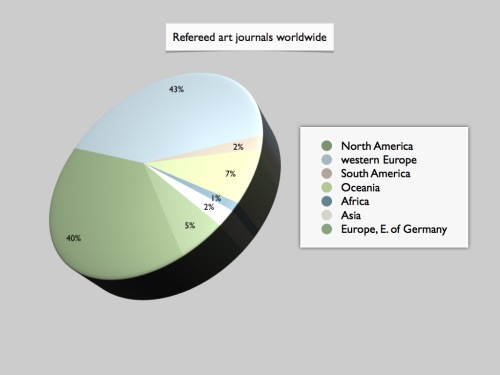

Some of the same dataset as a pie chart:

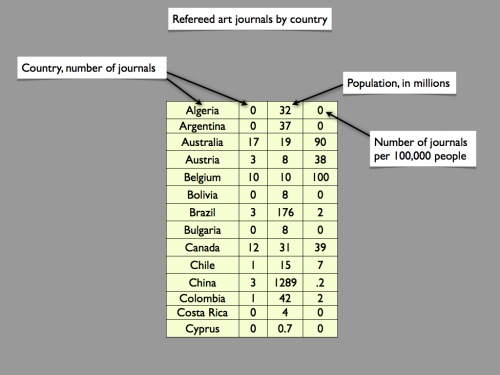

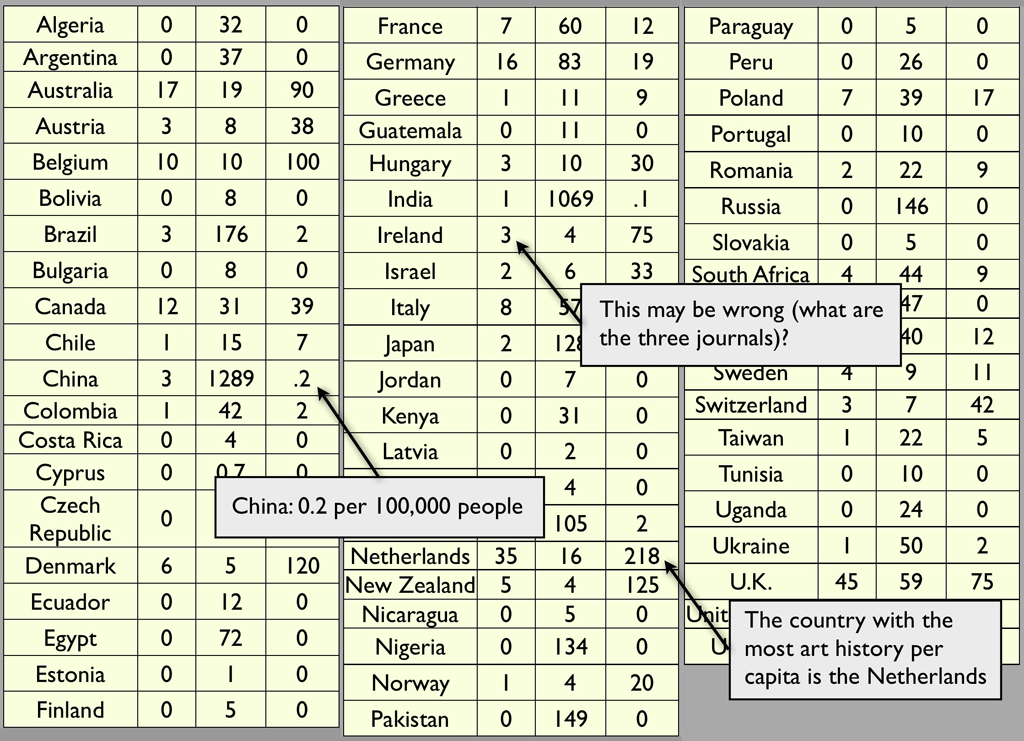

Even in c. 2007 there were many inaccuracies. Here, for example, Portugal is missing its refereed journal; Ireland may be over-counted. This is one of my favorite graphics to show in lectures, because each time something on it is found to be in error. (In the Courtauld, someone questioned the count for Slovakia; in Singapore, someone questioned several Asian countries…) But each time, the plausible corrections have been close to the figures here, so I think it might be safe to say they are roughly correct.

Incidentally: the Netherlands “wins” with the most art history per capita. When I gave this material in Leiden, some people in the audience applauded, but in Utrecht there was some amusement: why, someone asked, did the Netherlands need quite so much art history?

The data indicates the relatively small proportion of the Chinese public that is involved with art: the size of the art scene there, as John Clark has observed, is related to the overall population. Yet the data cannot be uniformly interpreted, because reviewing is culturally relative. Some countries, like China, have adopted it mainly in the sciences, where international collaborations and comparisons are more common.

This kind of data can help suggest patterns of emulation and resistance: places where institutions are more likely to form departments that identify themselves as art history, or that practice peer reviewing. These statistical questions are developed as insitutional histories in the essay, and in The End of Diversity in Art Historical Writing.

One Response